Birra Nursia, after the earthquake

/The birthplace of St. Benedict, after 2016's aftershocks.

Tis the time of giving. So I have a suggestion for a win–win gift: an order of beer from Birra Nursia, a monastic brewery in Umbria. Someone special will get some fabulous beer. At the same time, you’re helping the monks rebuild their monastery, destroyed by last year's earthquake. (If you don't like beer but want to offer some support, donations are welcome!)

A special-edition label for beer that was safe inside the sturdy fermentation tanks during the earthquake. I shot this at Il Cenacolo, a wonderful, homey restaurant in Norcia that Fr. Martin had recommended.

I first learned about Birra Nursia at a Slow Food/Salone del Gusto seminar on monastic beers in September 2016. Birra Nursia’s blonde ale was quite good indeed, but their backstory was even better: The brewers were young American monks who'd somehow made their way to this remote monastery in Umbria’s Sibylline mountains. Their town, Norcia, had been rattled the preceding month by an earthquake, but the historic monastery—birthplace of St. Benedict, founder of the Benedictine Order—had cracked but not toppled.

I decided then and there that this was a story worth pursuing and vowed to visit the next time I was in Italy.

But one month later, in October 2016, aftershocks shook Norcia to its foundations. The monastery crumbled. The historic basilica too, except for its façade.

Nonetheless, the monks’ website said they’d rebuild and carry on—and beer would be part of their efforts to finance the reconstruction.

Eight months later, I paid a visit. The resulting feature story was published in Tastes of Italia, which you can read below.

What follows are some of my photos that didn’t make it into print. Read the pieces together to get a better understanding of the devastation—and the heroic rebirth.

The main city gate of Norcia

On the drive from Perugia to Norcia, I started to see signs of the earthquake a good 20 miles from my destination—farmhouses with crumbled walls, wood struts supporting facades, swaths of road with recent repairs.

Arriving in Norcia, I drove around the medieval city walls. Whole sections had collapsed and were simply piles of stone. The main city gate (above) suffered damage too, but repairs were well underway—a considerable task.

The police office.

Inside the main city gate, buildings were in various states of distress. The carabinieri (police) office was still barricaded, plaster fallen from its facade.

Norcia's main street.

Scaffolding in wood and metal propped up numerous buildings that were still in a questionable state.

While I saw some tourists, numbers were well below the norm. According to one restaurant owner, even if tourists came, there was no place for them to stay, since most hotels were closed. For a city like Norcia, so dependent on tourism, this compounds the damage.

The main square with basilica and statue of Saint Benedict.

It's just a short walk to the main piazza. It was here that St. Benedict was born in 480 AD, and a basilica and monastery in his name grew in the years hence, drawing a steady stream of pilgrims.

Behind that facade, nothing remains of the basilica—a heartbreaking sight. And while surrounding buildings look intact, they're not. Cracks in the foundation make them unsafe to enter until significant repairs are done.

I attempted to explore the town, entering by another city gate, but was thwarted by one Zona Rossa (Red Zone) after another, which prohibited access to entire blocks.

The basilica bell tower shows the types of cracks that affect much of the centro. Unfortunately, it's not like pottery that you can simply glue together.

The basilica's rose window

By some miracle, the basilica's rose window survived the earthquake and aftershocks. It's this window that's pictured on every label of Birra Nursia—and has been since the monks started brewing in 2012.

The interior of a butcher shop.

Across the street from the basilica, this butcher shop looked like the earthquake happened yesterday. In fact, much of the town's center was evacuated after the initial quake in August 2016, which is why more deaths didn't happen during the severe aftershocks.

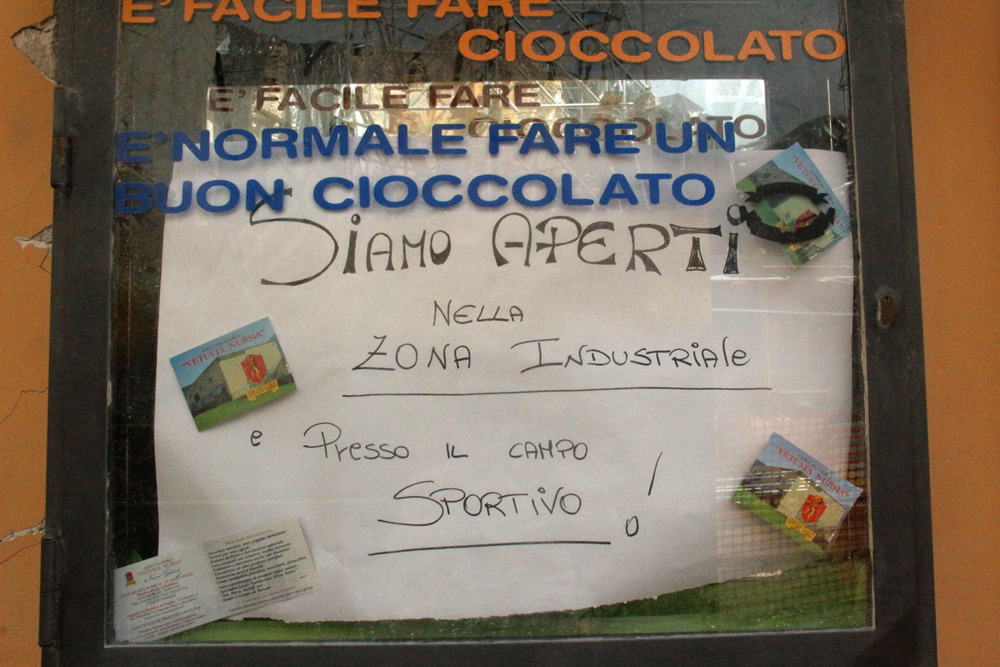

Shop signage: "We're open in the industrial zone, next to the sporting field!"

Many shops had relocated to temporary structures outside the city walls.

I noticed armed policemen posted at various points around town. Near another butcher (Norcia is renowned for its salumi), a young officer was trying to pet a couple of stray dogs. One had a collar, but was dirty and clearly homeless. Another was an adolescent pup, still in its eager goofy stage.

"You should adopt them," I said in Italian.

"Magari," he said. If only. "This one has a collar, but we don't know who the owner is."

More collateral damage that grips your heart.

A view of Norcia from the new monastery grounds.

My appointment was outside of town. The monks had essentially been booted out of the monastery ruins in Norcia's centro; they'd never owned that property and the parish wanted it back post-earthquake. So they're rebuilding up the hill.

The monks celebrate a wedding anniversary.

My interview was delayed by a special service the monks were performing for a local couple celebrating their 25th anniversary. It was held in their new chapel, a simple wooden structure that was the first thing to be erected on the grounds. It was partially subsidized by the Leffe, a monastic brewery in Belgium that has been their biggest reconstruction donor to date.

Afterwards, a monk wearing industrial noise protectors rang a large bronze bell rescued from the basilica, which hung from a wooden armature next to the chapel door.

The monks' dorm and kitchen.

On either side of the new chapel were signs of the monks' uprooted life. To the right were two prefab, disaster-relief housing units, where the 14 monks live and eat. To the left was an old, abandoned Franciscan church and convent. It too was partly felled during the earthquake. But the monks have gotten permission to clear the rubble and hope to turn what remains into a new monastery and church, "bigger than the one in town," says Father Martin.

Birra Nursia's temporary sales office.

Finally it was time to talk. Brother Martin escorted me to their new sales point, a base-bones trailer. It's open on weekends for local beer lovers and restaurants to pick-up orders. While the monks haven't resumed brewing yet, they're selling the beer that was safely stored in their warehouse and in the brewery's fermentation tanks.

Texas native Father Martin, in charge of brewing operations

It was fascinating to get the story of how this native of Fredricksburg, Texas, wound up at the Monastero di San Benedetto. (You'll have to read my article for that.)

I would love to have talked to every one of the monks, as each had followed his own, unique path to monastery life in these hills. Alas, all were eating lunch with the anniversary couple and friends. After Fr. Martin patiently answered my questions, he too zipped off to join the festivities.

Courtesy Monastero di San Benedetto

I have to finish with the most optimistic shot of all, which comes courtesy of the monks. It documents the blessing on the land where the new brewery will be constructed, next to the sales trailer. A blessed day indeed.

I hope to return someday and find it all shiny and new, churning out enough beer to keep this monastery going.

In the meantime, I put in my order, a little holiday present to myself—and to the monks.